In November of 2002, I accepted the position of Chief of Police in the small urban city of Fitchburg, Massachusetts. Fitchburg is a city of 40,000 people located in North Central Massachusetts. It is a typical old New England industrial city that never made the transition to a modern or hi-tech economy. As a result it has been economically depressed for many, many years. The lack of growth and prosperity in the city has resulted in a depressed real estate market that has made it an affordable place for immigrants to live. Along with these changes in demographics, Fitchburg has seen a rise in poverty and a serious drug problem with the accompanying violent crime.

When I was formally introduced as the new police chief to the public at the Mayor’s press conference, the Mayor stated that I was to “lead the war on crime and drugs”. This was the first time that I had heard this political statement and I interpreted it to mean a stepped-up, comprehensive enforcement policy that would drive crime and drugs out of the city. Over the next four years drug enforcement policies were expanded, but this measure alone did not lower the crime rate

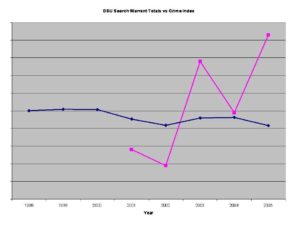

Most of the crime that was occurring seemed to be drug-related in one way or another. When I took over as police chief, one of the first things that I did was to form a regional task force of surrounding cities and towns to join in the enforcement of preventing narcotic trafficking and violations (. Over a two-year period, drug enforcement with search warrants increased over 400% (from 21 per year to over 100 per year). Similarly, seizures of the amounts of illegal drugs and confiscation of money and assets of drug dealers also increased, which was reflective of the increase in enforcement.

During this time period, motor vehicle enforcement escalated dramatically as did enforcement for serious and minor crimes. After a two and a half year period, we were able to graph an astounding increase in enforcement rate but the overall crime rate remained the same. Despite our “outstanding” increase in effort, there was no appreciable difference in the crime rate.

During this period, the murder rate in the city rose to a higher per capita rate than any other city in the state. There were six murders during my first 18 months as chief of police. An obvious fact jumped out at me in these murders in that five out of the six murders were minorities killing other minorities.

In one instance, I experienced a very revealing incident that became symbolic of why the crime rate continued to stay the same despite our efforts. One Christmas, I received a phone call at my home from the police department. I was informed that two people had been murdered with a knife and that another person (a woman) was not expected to live… All the participants involved in the crime, victims, witnesses and perpetrator, were all Latino.

Upon receiving this information, I responded to the police station. It was about 4 a.m. when I arrived. The police station was brilliantly lit up, reflecting the busy activity inside of the building. When I entered the building, I observed several of my officers rushing about, doing reports and working on the preliminary investigation. I also observed that these officers were primarily young and newer officers as is the custom for working the late night shift. They were performing in a very professional manner and doing their jobs with accuracy and efficiency.

At this point, I went to another area of the building and met with the Detective Supervisor Investigator. As police chief, I asked him if there was anything that I could do that would make his job easier in the investigation, and he said “no, not at this time.” A short while later, he came to my office and asked me if I could meet with one of the victims’ families. I immediately answered that I would, knowing that this would relieve him of the emotional and time consuming burden of dealing with the grief of the family.

I asked him where the family was and how long had they been waiting. He responded that they were in the lobby of the police station and had been there for about an hour and a half. I located one of my Latino police officers that was working and asked him to assist me in translation and cultural matters with the victim’s family. We then went to the lobby of the station and met with the mother and two sisters of one of the victims. I introduced myself as the Chief of Police to the family and asked them to follow me. I took them to a small private lounge area located next to the detective bureau. I observed that all of them had some blood on them and it was apparent that they were at the scene of the crime at some point.

Once inside the room, I observed that they were visibly upset and I asked them what I could do to help them. Only one of the women spoke English, a teenage girl. She said that her mother wanted to know what was going on with her son. I told her I would find out for her and walked out of the room and asked the detective supervisor who told me that the son was dead. He and I agreed that I should notify the family members, as a number of hours had already passed. I know that everyone was busy investigating this event but I was surprised and disappointed that the family members were not informed sooner of the death of their Loved one.

I then went back into the room to tell the family. I had begun to tell them the news when State Police Detective walked into the room. I immediately introduced him to the family and then proceeded to tell them that their son/brother was dead. Upon hearing this news, the family members began to cry and wail. The mother stood up, ran into the detective bureau, hurled herself on the floor and became hysterical. The other women acted in a somewhat similar manner. After about five minutes, they all sat down in the lounge area and began to weep and hold each other.

I left the room with the officer who had accompanied me and I asked him if there was anything I could have done differently and he stated, “No Chief, you just have to let it go.” I then went over to the State Police Commander who I had introduced to the family. (Note: In Massachusetts, the state police assist the cities and towns of the state on murder charges and have jurisdiction of the investigation.) I said to the Commander, “I am sorry you had to walk into that situation.” He then said to me, “Chief, I really wish you had not talked to them before we talked to them.

At this point, I realized that even though all of the police officers and state police officers involved in this incident were all doing an excellent “technical” investigation, there was a communication process that was lacking for the victim’s family. I wondered how we would have responded if it was the president of the local university’s family waiting in the lobby that night and if we would have found time to speak with them first.

After this incident passed, I began to look for patterns within the police department and found out that 12 of our police officers were currently being sued by members of the Latino community for different forms of alleged abuse. In none of these instances were the police found responsible for wrongdoing. I became obvious to me that something more was at work here than just that murders had been committed and lawsuits were constantly being filed. There was a serious disconnect and lack of communication with Latinos and other minority groups in the community. Without contacts or relationships within the community, it was not surprising that the same patterns of crime kept recurring. As chief law enforcement officer, it was my duty to find out why this was happening and make a plan for resolving it

My experience told me that the best way to do this was to actively reach out to the Latino members of the community, and try to engage them in solving the problem with us. It was at this time that I met Sayra Pinto, a Latino community activist and Executive Director of the Twin Cities Latino Coalition. She had invited me to join the coalition in order to promote success of Latino students in our school system. I was very impressed as Sayra described the work she had done with at-risk youth with the ROCA) program in Chelsea, Massachusetts; ROCA is a nationally recognized program that works with inner city gang leaders and members to transform their lives and become leaders and mentors for at risk youth in their communities. In the course of this conversation, we discovered our mutual interest in the systems approach to problem solving.. Both of us were committed to getting to the root of our respective crime problems. Merely identifying the symptoms was no longer an option. In a subsequent meeting we discussed the fact that the dropout rate at the High School for Latino students as more than 40 %. I also became aware that over 50% of the students in our kindergarten system were Latino. The Latino population was continuing to grow, and if things did not improve it would result in a continuation of the current failure and increasing crime rate. I knew that when at-risk students drop out of school their chances of being involved in crime and of being incarcerated rose significantly. National studies consistently back this conclusion. 1( In effect, the failure of these children in school was highly correlated with the higher risks for poverty and repeat involvement in crime. Again, national studies bear out this correlation. 1

Major Impact of Systems Thinking

Sayra invited me to a conference that was given by the Society or Organizational Learning in Boston, Massachusetts. It was at this conference and also through my individual university program in organizational development that I was further exposed to Systems Thinking. This model challenges a manager to look at the overall problem in a systematic, interrelated way rather than looking at it as a series of isolated events. Applying a Systems Thinking approach to the crime problem in our city meant that we were committed to identifying the root causes of crime and calling attention to the non-police related and less obvious issues that continued to maintain the failure of the system.

The flat line is the crime rate and the pink lines are indicative of drug enforcement.

Applied Systems Thinking uses specific tools known as archetypes that help determine what kind of patterns are occurring in a chronic problem. For the criminal justice system, enforcement appears to be good practice, but on closer examination, it can be demonstrated that enforcement over the long term can in fact worsen or deepen the problem, making it even harder to break the cycle or response. This is in an example of one archetype (known as “addiction to practice”) that represents a simple reinforcing loop. The only way to interrupt this cycle, is to introduce a balance in the process or a balancing loop. This information clearly told me that although our efforts in enforcement were highly successful on paper, we actually were not impacting the crime rate. Drugs were flowing at the same rate they had been and the Latino community was becoming more and more isolated.

This information was indeed troubling and far beyond the scope of the local police chief. At this time, The Sentinel and Enterprise, local newspapers with a circulation of about 125,000 readers, ran a series of articles called “Decades of Addiction.” The reporting painted many of the people involved in drugs as being Latino and (in my opinion) only served to deepen blame and resentment towards Latino people in the community. After the series was printed, the newspaper editor contacted me and asked me if I would be willing to put together a regional task force to address the crime and drug issues. His newspaper offered to put $5,000 toward a program that would help the communities alleviate the crime and drug problems.

I agreed to participate and help form the task force that was chaired by two local university presidents. We invited all the local police chiefs, probation, parole, prison, and social workers, school superintendents, teachers, private citizens, and minority representatives for a total of about fifty task force members.

It was at this time that Sayra Pinto and I convinced the task force to employ a Systems Thinking model to examine the deep-rooted problems in our communities and especially to expose the “blind spots” that we may not be seeing as contributing or causing the problems. This effort included a 12-hour workshop on Systems Thinking that was given to the group by outside consultants Sara Schley and Joe Laura of Seed Systems. After the basics of the process were understood, the task force, through diagnostic diagrams and discussion, identified two key issues [(1) lack of economic development and 2) institutional racism] as being deep seated issues in the community that needed to be addressed before the community could move forward to solving the drug and crime problems in an effective and lasting way.

Systems Thinking: Future Police Perspective

The culmination of the work that was done by the task force by applying Systems Thinking expanded the responsibility of solving the community drug and violence problems that, up to this point, had been perceived as “police problems” to include other stakeholders in the community. The police would continue to do their work in enforcement but also incorporate prevention and intervention strategies for at-risk youth. Other areas of the community were required to share more of the burden and look at the problems in a “systems” way. One result was for the stakeholders of the task force to look at applying resources towards the roots of crime. The task force raised $50,000 to use for summer jobs for at-risk youth or youth who were likely to offend in the future. The City of Fitchburg saw a decrease in violent crime over the summer. Overall, for the year 2006, violent crime fell by 14% and was followed by an additional 4% reduction in 2007 during the time that this “systems” strategy was implemented.

Although a direct cause and effect between a systemic approach to fighting crime and the resulting drop in crime is not possible, many signs emerged during this period that gave positive indications that this process was effective. For the first time, the public institutions and private companies within the region were engaged in conversations that questioned past practices of seeing crime as a single issue and moved toward seeing it as a more community centered problem. In addition, (see side note) this resulted in many deep conversations and self-reflection. I began asking myself, “What do I do to make the problems worse in the City?” rather than blaming others for failure. I began to look more closely at my hiring practices to uncover blind spots that unintentionally allowed the system to preserve its ways of exclusion and failure of the Latino community.

The following diagram illustrates how the strategy of the Fitchburg Police Department contributed to this reduction in crime. It is a comprehensive model that factors in many stakeholders and efforts to reduce crime and its root causes in the community.

Another outcome was the police forming a regional partnership with the Twin Cities Latino Coalition and successfully applying for and receiving funding to work with at-risk youth to deter them from crime. We also began looking at expulsion practices in the schools and introduced a restorative justice model to not only hold the students accountable but to solve issues and keep them in school.

Another outcome was the police forming a regional partnership with the Twin Cities Latino Coalition and successfully applying for and receiving funding to work with at-risk youth to deter them from crime. We also began looking at expulsion practices in the schools and introduced a restorative justice model to not only hold the students accountable but to solve issues and keep them in school.

The task force also began a community dialogue on race and race relations that has resulted in the forming of effective multi-racial committees to look at deep-seated racial problems in order to dispel the common myth that “minorities cause crime.” One of the results of this work has been a much greater presence and participation of the minority community in local affairs that culminated in the election of the first minority woman mayor in the city’s history.

Having experienced the effectiveness of Systems Thinking applied to police work in my own police department I was surprised that this practice was not more widely used in police work in the United States. I had attended several national police conferences and was never aware of any application of Systems Thinking being used in policing in the United States. An online search revealed that some research papers have been written on the topic of Systems Thinking and policing but from what I have read it was theoretical and mostly written about in other countries such as the UK, Singapore and New Zealand. In fact, it wasn’t until I attended a Systems Thinking conference sponsored by Pegasus that I became familiar with the fact that the Singapore Police Department trains and uses it to solve community policing and organizational problems within their police department in a highly effective way. When I attended the first International Chiefs of Police Conference in the Middle East North Africa Region in Doha in November 2008, I was pleased to see that the Singapore Police were presenting on the success of their community policing program that is based on a Systems approach. At the conference t I learned that it had now been ten years since a Systems Thinking approach to identifying problems had become routine in the Singapore Police Department. In fact, the practice had been so successful in resolving issues, that the Police Commissioner was elected to head the prestigious international police agency, Interpol.

There is no question in my mind that the use of Systems Thinking is a comprehensive and holistic way of addressing crime and organizational problems in policing today. It can help identify hidden blind spots and the best leverage points for change. This approach has proven to be more effective in addressing the most relevant issues and in reducing the costs associated with modern police operations. It can also help to redirect resources needed to address the “hidden” causes of crime in order to solve the overall problems. The application of this process was both a revelation and a challenge for me. It revealed that the past practice of responding to crime without taking into consideration some of the less obvious contextual factors was destined for failure, but also that breaking the cycle of police responsibility for reducing crime would be a very difficult challenge – with regard to local leadership who had become convinced of the the idea that crime was just a police problem.

The way in which crime will ultimately be managed in the Fitchburg Police Department is an ongoing process. I have now retired from my position as police chief,, but my experience with Systems Thinking has given me valuable insight about looking at the world from an entirely new perspective. At the community level , it has taught me that relying on a single force, in this case the police department, and defaulting to quick and easy fixes is short sighted, and can result in unanticipated and costly consequences. In other words, it can often result in failure. In the end, it will be our ability to engage people in the community in on-going dialogue and our ability to work consistently with them to identify the root causes of chronic criminal activity .It is this approach that will lead to desired and more sustainable results and ultimately, in a healthier, and more engaged community.